LINGUISTIC PROGRAMME IN CASTILLA-LA-MANCHA: A STUDY OF TEACHERS´,

PARENTS´, AND STUDENTS´ ATTITUDES TOWARDS BILINGUALISM IN SECUNDARY

EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS

LOS

PROGRAMAS LINGÜÍSTICOS EN CASTILLA-LA-MANCHA: UN ESTUDIO DE LAS

ACTITUDES DEL PROFESORADO, FAMILIAS Y ALUMNADO HACIA EL BIBLINGUISMO EN

INSTITUTOS DE EDUCACIÓN SECUNDARIA

sevillanieto@yahoo.es

Jelena Bobkina, Technical University of Madrid, Spain

jelenabobkina@hotmail.com

|

Sevilla, A. & Bobkina,

J. (2016).

Linguistic programmes in Castilla-La-Mancha: A study of teachers´,

parents´ and students´ attitudes towards bilingualism in Secondary Education

Institutions.

Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, Vol. 7(1). 210 – 229. |

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest

in bilingual education in Europe in general, and particularly in Spain. Thus,

in barely fifteen years, the number of bilingual centers in public and private

education has increased dramatically throughout the country. Numerous bilingual

programmes have been implemented in different autonomous communities in Spain,

being the most referential those one articulated in Madrid, Andalusia and the

Basque country.

Not surprisingly, bilingual education that is

characterized by teaching of different curricular areas through a foreign

language has become a popular issue throughout the Europe (Nieto Moreno de

Diezma, 2016; Nikula, Dalton-Puffer, & García, 2013; Ruiz de Zarobe &

Jiménez Catalán, 2009). Many European Union institutions have adopted CLIL as

an educational model to ensure students´ language proficiency in several

languages. Being the most common form of bilingual education in Spain, CLIL has

also has attracted a special interest of a great number of researchers in this

country (Lasagabaster & López Beloqui, 2015).

Nevertheless, most of the research done in bilingual

education has focused on the students’ linguistic competence; that is, the

effectiveness of different bilingual programmes (Admiraal, Westhoff, & de

Bot, 2006; Dalton-Puffer, 2008). But less study has been done on non-linguistic

outcomes of bilingualism, such as attitudes, cultural values, self-concept and

beliefs (Coady, 2001; Gerena & Ramirez Verdugo, 2014). Besides, most

investigation is centered on those regions that have been among the first ones

to pilot bilingual projects, such as Madrid or Andalusia (Alonso, Grisaleña,

& Campo, 2008; Casal & Moore, 2009), leaving far behind other

communities as it might be the case of Castilla-La Mancha o Castilla-Leon.

To give response to this demand, the present research

aims at analyzing students´ attitudes towards bilingualism and foreign language

learning in Castilla-La Mancha, that is betting hard for implementation of

bilingual education. In particular, the study seeks to determine the

relationship between bilingual education and students´ self-concept as well as

their motivation towards language learning. Besides, teachers´ and parents´

attitudes towards linguistic programmes and their effect on students´

motivation are analyzed.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. A brief

background to bilingual education in Castilla la Mancha

The region of Castilla-La Mancha enrolled in the

project in 1996 with 7 schools that initially participated in the programme. In

2002, Spanish/French bilingual sections were created in some primary schools.

The programme of the integrated curriculum covered from the preschool level to

the end of the secondary education and aimed at providing a model of bilingual

education based on the curricular integration of two languages and their

cultures.

In 2014, a new legislation regulating bilingual programmes in Castilla-La Mancha was enacted (Decree 7/2014, Order 16/06/2014) in order to create a global plan for plurilingualism. Linguistic programmes started to be classified into three categories according to the number of content subjects taught through a foreign language:

- Initiation

programmes with one content subject taught through a foreign language at each

of the four years of secondary education.

- Development

programmes with at least two content subjects through a foreign language at

each of the four years of secondary education.

- Excellence programmes with three content subjects through a foreign language at each of the four years of secondary education.

Students’ participation in linguistic programmes in

secondary education is voluntary and depends entirely on their own decision

regardless the fact whether they have been enrolled previously in bilingual

programmes or not. Teachers may also recommend students to enroll or to quit

the linguistic programme according to their academic results.

Teachers involved in the programme

should have at least a B2 language certificate as established by the European

Common Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001), although

those schools with a linguistic excellence programme must have at least one

teacher with C1 language certificate.

2.2.

2.2 Attitude towards bilingualism

Immersion and dual-education programmes and their

effect on students´ motivation have been studied extensively in the

North-American context. Thus, Craig (1996) examined the attitudes toward

bilingualism of English and Latino parents in the USA whose children were

involved in Spanish-English immersion programmes. The study revealed that

parents considered two-way immersion programmes to be highly positive in terms

of pluriculturalism, cultural enrichment and educational excellence.

Similar results were described by Cazabon, Lambert,

and Hall (1993) who analyzed a two-way bilingual programme developed in the USA

which combines bilingual education for limited-English-proficient students and

language immersion for native English speakers. The results confirmed students´

and parents´ satisfaction with the programme from both academic and social

point of view.

The influence of social and demographic variables on

students´ attitude towards bilingualism was examined by Galvis (2010) who

analyzed the attitude of high school students in California toward

English-Spanish bilingual programme. The research demonstrated that the English

speaking majority showed a less positive attitude than the Spanish speaking

minority.

When analyzing the results of the studies done in this

area, we can see that most of the researchers agree on positive attitudes

towards bilingual education among students (Cazabon, Lambert, & Hall, 1993;

Galvis, 2010; Gerena & Ramirez Verdugo, 2014; Ordóñez, 2011; Ramos, 2007),

parents (Cazabon et al., 1993; Craig, 1996), and teachers (Fernández, Pena,

García, & Halbach, 2004; Gerena & Ramirez Verdugo, 2014; Ordóñez, 2011).

3. Method

In order to unveil students´, teachers´ and parents´

attitude towards bilingual programmes recently introduced in Castilla-La

Mancha, three different questionnaires have been designed and administered to

students, parents and teachers. All questionnaires included a combination of

closed and open questions.

The first part of the questionnaires based on 1 to 5

Likert scale aimed at evaluating respondents´ attitude towards English

language, linguistic programmes, instrumental orientation, parental

encouragement, multiculturalism and integrative orientation. Additionally,

teachers were asked to evaluate the availability of teacher training programmes

on bilingual education, as well as the teaching materials for bilingual

schools.

Moreover, the second part of the questionnaires,

consisting of a set of open questions, allowed participants to express their

opinion regarding positive/negative aspects of the linguistic programme.

Results have first been analyzed quantitatively to be

later on presented and discussed in the Results section of the present study.

The conclusions and the pedagogical implications derived from the discussion of

results can be found in the final section of the paper.

3.1. Participants

Two

secondary education schools located in the south of Castilla-La Mancha have

taken part in the study. Students’ questionnaires were delivered to 62 students

from the 3rd and the 4th grades of the secondary

education. Similarly, the same number of questionnaires was administered to the

parents of those students who took part in the research.

Teachers’ questionnaires were delivered to 15 content subject teachers involved in the schools´ linguistic programmes. The subjects covered include Maths, Technology, Information Technology, Physics and Chemistry and Biology and Geology.

3.2. Instruments

The second questionnaire designed to collect the data

related to the teachers´ opinions was organized in a similar way. In addition

to those sections included in students´ questionnaire, teachers were asked to

evaluate the methodology used in bilingual programmes, the availability of

teacher training programmes on bilingual education, as well as the teaching

materials for bilingual schools. The items included in each of the sections

were the following: (1) Attitude towards

English: 1.6. I find difficult to motivate my students to study

non-linguistic subjects in English. 1.7. My students show positive attitudes

towards the use of English in the classroom. 1.8. My students feel anxious when

they are asked to speak in English. (2)

Attitude towards linguistic programme: 2.1. The bilingual programme

contributes improving the general quality of education. 2.2. The bilingual

programme contributes improving the level of English of the students. (3) Parental encouragement: 3.5. Parents´ involvement in the bilingual

programme is of outmost importance. (4)

Methodology, teacher training and materials: 4.3. Teaching a non-linguistic

subject in English requires an important change of methodology. 4.4. The

teacher training programmes on bilingual methodology available for teachers are

adequate. 4.9. The materials available for teachers of non-linguistic subjects

in English are adequate. There was a total of 9 items scored on a five-point

Likert Scale (from 1 = Totally disagree to 5 = Completely agree). The last

section consisted of a set of 2 open questions dealing with positive and

negative aspects of the bilingual programme.

The third questionnaire designed to collect the data

related to parents´ opinions included 3 sections. The first two sections were

aimed to evaluate parents´ opinion towards English and linguistic programme.

The items included in each of the sections were the following: (1) Attitude towards English: 1.1. I

encourage my child to use English in his/her free time. 1.2. It is important to

study English. 1.6. The knowledge of English will be helpful for my child´s

future work. 1.7. It is important for my child to continue studying English

after the secondary school. 1.9. It is important for my child to know the

culture of the English-speaking countries, (2)

Attitude towards linguistic programme: 2.3. I consider that the bilingual

programme has contributed positively to the level of English of my child. 2.4.

When my child started the bilingual programme I was worried that it would

affect negatively his/her grades. 2.5. The bilingual programme motivates

students to study English. 2.8. Students of bilingual programmes have an

advantage over those studying in monolingual programme. 2.10. The bilingual

programme has improved my child ´s attitude towards English. There was a total

of 10 items scored on a five-point Likert Scale (from 1 = Totally disagree to 5

= Completely agree). The last section consisted of a set of 2 open questions

dealing with positive and negative aspects of the bilingual programme.

3.3.1.1. Questionnaire. Likert Scale items

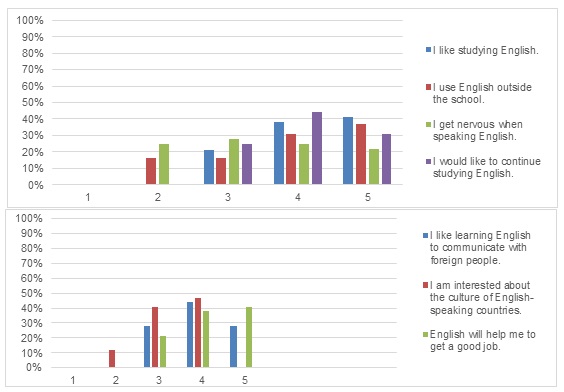

Regarding the first section of the questionnaire, the

students expressed highly positive attitude towards English language (see

Graphs 1 and 2). Thus, about 79% of respondents showed a great interest in

studying English in general. The same percentage of students agreed on the

necessity of having a good level of English to get a better job in the future.

In fact, 75% of students stated that they would like to

continue studying English after finishing their secondary school studies.

Additionally, about 72% consider English to be an

excellent tool of communication. Thus, around 68% of students reported that

they use English outside the classroom. What´s more, about 50% of the

respondents do not get nervous when speaking English.

Nevertheless, these positive results come to be

shadowed by the fact that relatively low percentage of the respondents (less

than 50%) showed their interest towards the culture of the English-speaking

countries.

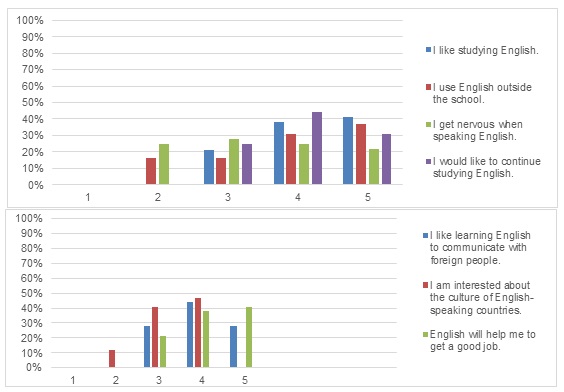

As far as the students´ attitude towards linguistic

programme concerns, it is worth noticing that students´ general assessment was

mostly positive (see Graphs 3 and 4). Thus, 72% of the participants affirmed

that they liked studying content subjects in English. What´s more, 79% of them

considered the contents studied in English to be useful in their future. This

is quite related to the fact that 68% of the students enrolled in the

linguistic programme consider themselves to be in a more advantageous position

if compared to students of monolingual schools.

Quite surprisingly, most of the respondents (72%) do

not consider studying content subjects in English to be difficult for them.

What´s more, around 62% of the students reported that the use of English as a

vehicular language has not affected their grades. Equally revealing is the fact

that a high number of students expressed their desire to have more subjects

(59%) and more languages (65%) to be included into the linguistic programme.

Parents are external agents who play an essential role in encouraging their children to learn English and transmit positive attitudes and opinions toward the foreign language and the culture which it represents. As seen from the table below, students´ answers clearly indicate that their families consider that learning English is important and, therefore, encourage them to study English.

Table 1.

Students´

assessment of self-attitude toward parental encouragement

|

Attitude toward parental encouragement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

7. My family considers English to be an important issue. |

0% |

0% |

0% |

56% |

44% |

|

8. My family encourages me to study English. |

0% |

0% |

0% |

56% |

44% |

3.3.1.1. Questionnaire. Open questions

On the negative side, some students pointed to the

fact that studying non-linguistic subjects in English was more difficult for

them and required some extra time for preparation.

3.3.2. Analysis of teachers´ questionnaires results

3.3.2.1. Questionnaire. Likert Scale Items

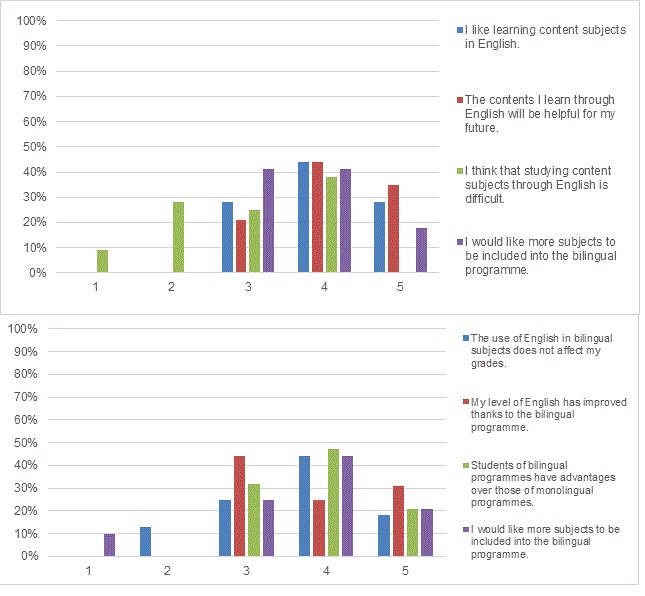

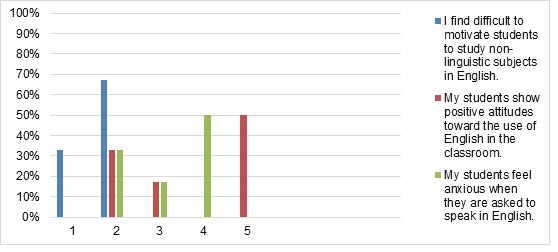

Surprisingly, only 50% of the participants agreed with

the statement that their students showed positive attitude toward the use of

English during the classes, while 33% of them disagreed. This fact contrasts

with the data received from the analysis of students´ questionnaires, where 72%

of the respondents declared that they liked studying content subjects in

English.

Finally, about 50% of the teachers declared that they

found their students insecure when speaking English. These results coincide

with the data obtained from the students´ responses, where 47% of the

participants recognized that they got nervous when speaking English.

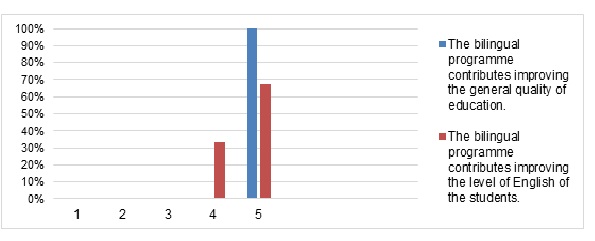

Results obtained in the present section of the questionnaire reveal the fact that 100% of the responders consider the linguistic programme to be the one contributing positively to the general quality of education (see Graph 6). In fact, 100% of the teachers polled reported that the linguistic programme improved the students´ level of English. Surprisingly, this data contradicts the information obtained from the students´ questionnaire according to which only 56% of the respondents consider the linguistic programme has improved their level of English.

Graph 6. Teachers´assessment of students´attitudes toward the linguistic programme

As it can be seen from the table below, 83% of the

teachers consider parental encouragement essential for their students´ success.

Table 2.

|

Parental encouragement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

5. Parents´ involvement into the bilingual programme is of outmost

importance. |

0% |

0% |

17% |

50% |

33% |

Regarding the methodology used for teaching

non-linguistic subjects through English, teachers´ responses were rather

contradictory (see Table 3). 33% of the teachers reported that a change of

methodology was necessary when teaching content subjects through English, meanwhile

17% declared that no change was necessary.

In the same vein, teachers´ responses on questions 4

and 9, dealing with teacher training courses and adequate teaching materials,

differ a lot. Only 16% of the participants declared to have had adequate teacher

training courses, meanwhile the vast majority of teachers (67%) pointed to the

lack of training.

|

Methodology, teacher training and materials: |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

3. Teaching a non-linguistic subject in English requires an important

change of methodology |

0% |

17% |

50% |

33% |

0% |

|

4. The teacher training programmes on bilingual methodology available

for teachers are adequate. |

0% |

67% |

17% |

16% |

0% |

|

9. The materials available for teachers of non-linguistic subjects in

English are adequate. |

0% |

67% |

0% |

0% |

33% |

3.3.2.2. Questionnaire. Open questions

Among the major drawbacks of the linguistic programme, most of the teachers mentioned the lack of coordination with a language assistant due to the heavy workload. Additionally, some teachers declared that the use of English as a vehicular language led to the development of learning difficulties in case of some students. The lack of common assessment criteria regarding the use of English in non-linguistic subjects was the other aspect mentioned by teachers.

3.3.3.3. Analysis of parents´ questionnaires results

3.3.3.1 Questionnaire. Likert Scale Items

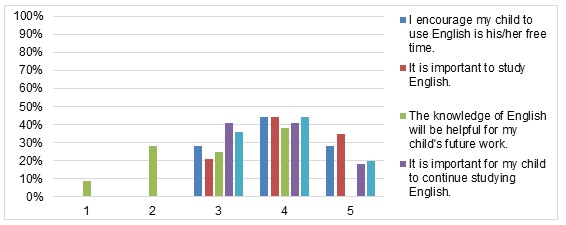

Parents are key agents in linguistic programmes as

they are the ones who take the decision of enrolling their children in the

linguistic programme. The results of the research clearly indicate that most of

the parents have a highly positive attitude toward English (see Graph 7). Thus,

100% of the respondents find English to be an important subject and consider

that the knowledge of English is essential for their children’s future jobs. In

fact, 60% of the parents actively encourage their children in studying English.

Not surprisingly, all of the participants indicate that they would like their

children to continue studying English in the future.

Graph 7. Assessment of parents´ attitudes toward English.

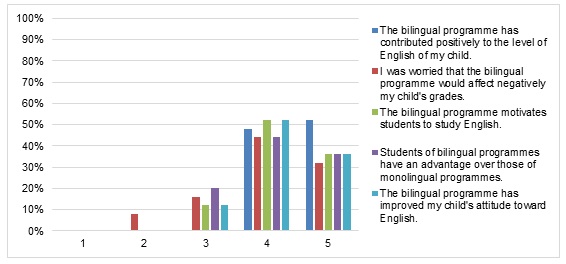

Regarding the parents´ attitudes towards the linguistic programme, as shown in the graph below, the parents´ responses were mostly positive. This comes supported by the fact that 100% of the respondents consider that the linguistic programme has contributed to the improvement of their children level of English. What´s more, 88% of the parents have noticed the increase of motivation toward the English language among their children, the fact that most of the respondents (78%) relate to their children involvement into linguistic programme. It is important to notice as well that 76% of the parents expressed their concern about the fact that the use of English as a vehicle language would affect negatively their children´s grade. Even though, 80% of the respondents declared that those students enrolled in the linguistic programmes are in a more advantageous situation compared to the rest of the students.

3.3.3.2. Questionnaire. Open questions

When commenting on the negative aspects of the linguistic programme, the most frequent comment dealt with the fact that the use of English as a vehicular language may affect negatively the students´ grades. Some parents expressed their preoccupation on the quality of specific contents taught through English and the lack of language assistants to support the programme.

4. Conclusions and pedagogical implications

To conclude, the overall results obtained from the research are rather

satisfactory as they reveal quite positive global outcomes. Most of the

students have reported to have a positive attitude towards English. This fact

is of outmost importance as the positive attitude enhances the successful

development of the teaching learning process within the linguistic programme.

This positive attitude of students toward English also explains the fact that

teachers do not find difficulties in motivating students to learn content

subjects through English.

In spite of the general positive attitude toward English, most of the

teachers recognize that some students feel rather reluctant to use English

during the lessons. Students’

attitudes toward the use of the foreign language during the lessons may vary

depending on the content subject and, even within the same subject, depending

on the specific topic of the lesson. We should bear in mind that, regardless of

students’ attitudes toward language or content, teachers have to use

strategies, activities and tasks aimed at motivating students to learn language

and/or content.

Both students and parents have recognized the importance

of studying English after finishing secondary school studies. In this sense,

the availability of the linguistic programmes on both upper-secondary and

vocational levels may contribute positively to students´ motivation.

Not only do parents recognize the importance of

English, but they also encourage children in their studies of a foreign

language. This parental encouragement is also confirmed by students’ and

teachers´ responses. However, the study has revealed that more emphasis should

be put on enhancing students to use English outside the classroom.

The instrumental motivation toward learning English is

clearly expressed by both students and parents. Both groups recognize the

importance of studying English as a chance to improve future employability.

Both students and parents were asked about the

integrative and multicultural orientation for learning English. Students stated

that they like learning English because it allows them to communicate with

people from different countries. However, when both groups were asked about the

importance of learning about the culture of English-speaking countries, neither

of them seem to consider culture as an important aspect of language learning.

As regards the students´ attitude toward the

linguistic programme, the fact that students are motivated to learn content

subjects through English is of paramount importance. The majority of

respondents reported that they like studying content subjects through English

and do not find it difficult.

All three groups were asked on the effect of the

linguistic programme on students´ level of English. It is interesting to notice

that the most positive appreciations were given by teachers and parents, who

declared that the programme is undoubtedly helpful in this aspect, whereas

students´ answers were not so straightforward.

Not surprisingly, all respondents stated that

bilingual students have advantages over non-bilingual students. Apart from the

clear benefits related to the language acquisition, the linguistic programme contributes

positively to the general quality of the education.

Among the main concerns expressed by parents is the

one related to the fact that the use of English as a vehicle language may have

a negative effect on students’ grades. Contrary to this expectation, most of

the students affirmed that the use of English in content subjects has not had

any negative effect on their academic results.

One of the important aspects of the linguistic

programme that has been highly criticized by teachers deals with availability

of adequate teacher training courses and teaching materials designed for

teaching non-linguistic subjects through English.

5. References

Admiraal, W., G. Westhoff, & de Bot, K. (2006).

Evaluation of bilingual secondary education in the Netherlands: Students’

language proficiency in English, Educational Research and Evaluation, 12, 75-93.

Alonso, E., Grisaleña, J., & Campo, A. (2008). Plurilingual education in secondary

schools: Analysis of results. International

CLIL Research Journal, 1 (1),

36-49. Retrieved from http://www.icrj.eu/11/article3.html

Baker, C. (2001). Foundations of bilingual education and

bilingualism. Clevedon:

Multilingual Matters.

Burgess, T.F. (2001). Guide to the design of questionnaires. A

general introduction to the design of questionnaires for survey research.

Information Systems Services: University of Leeds.

Casal, S., Moore, P. (2009). The

Andalusian bilingual sections scheme: Evaluation and consultancy. International CLIL Research Journal, 1 (2), 36-46. Retrieved from http://www.icrj.eu/12/article4.html

Cazabon, M., Lambert, W. E., & Hall,

G. (1993). Two-way bilingual education: A

progress report on the Amigos programme. Santa Cruz, CA, and Washington,

DC: National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language

Learning.

Coady, M. (2001). Attitudes toward

bilingualism in Ireland. Bilingual

Research Journal: The Journal of the National Association for Bilingual

Education, 25 (1-2), 39-58.

Content and

Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) at school in Europe (2006). European

Commission. Retrieved from http://www.eurydice.org

Council of Europe

(2001). Common European Framework of

Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: CUP.

Craig, B.A. (1996). Parental

attitudes toward bilingualism in a local Two-way immersion programme. The Bilingual Research Journal, 20 (3/4), 383-410.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2008). Outcomes and processes in

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): current research from Europe.

In W. Delanoy & L. Volkmann (Eds.), Future

perspectives for English language teaching (pp.139-157). Heidelberg:

Carl Winter.

Decreto 7/2014. Por el que se regula el plurilingüismo en la

enseñanza no universitaria en Castilla-La Mancha. Consejería de Educación,

Cultura y Deportes de Castilla-La Mancha, 2014.

Dobson, A., Pérez Murillo, M.D., & Johnstone, R. (2010). Bilingual

Education Project Spain. Evaluation report. Findings of the independent

evaluation of the Bilingual Education Project. Madrid: Ministry of Education of Spain and British

Council.

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in

second and foreign language learning. Language

Teaching, 31, 117-135.

Dornyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in Language learning: Advances

in theory, research and applications. Language

Learning, 53 (1), 3-32.

Fernández Fernández, R., Pena Díaz, C., García Gómez, A., & Halbach,

A. (2005). La implantación de proyectos educativos bilingües en la Comunidad de

Madrid: las expectativas del profesorado antes de iniciar el proyecto. Porta Linguarum, 3, 161-173.

Galvis, C. (2010). Actitud hacia el bilingüismo

inglés-español en estudiantes de secundaria norteamericanos. Revista

Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada, 8 (4),

3-16.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). The attitude/motivation test battery.

Technical report. Canada: University of Western Ontario.

Gardner, R.C.

(1985). Social psychology and second

language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward

Arnold.

Gardner, R. C.

(2001). Integrative motivation: Past, present and future. Temple

University Japan, Distinguished Lecturer Series, Tokyo, February 17, 2001;

Osaka, February 24, 2001. Retrieved from http://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/ GardnerPublicLecture1.pdf.

Gardner, R. C. (2004). Attitude/Motivation test battery.

International AMTB research project. Canada: University of Western Ontario.

Gerena, L., Ramírez Verdugo, M. D.

(2014). Analyzing bilingual teaching and

learning in Madrid. A Fulbright scholar collaborative research project. Education and Learning Research Journal,

8, 118-136.

Guía

del auxiliar. Programa de auxiliares

de conversación en España 2015/16. (2015). Madrid: Ministerio de Educación,

Cultura y Deporte, Gobierno de España.

Guía

del tutor. Programa de auxiliares de conversación en España 2015/16.

(2015). Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Gobierno de España.

Guía

del auxiliar de conversación de la Comunidad de Madrid 2015-2016.

(2015). Dirección General de Mejora de la Calidad de la Enseñanza. Consejería

de Educación, Juventud y Deporte. Comunidad de Madrid.

Guía

informativa para centros de enseñanza bilingüe.

(2013). Dirección General de Innovación Educativa y Formación del Profesorado.

Consejería de Educación. Junta de Andalucía.

Hernández, P. (2014, January 24). La Junta prepara un

ambicioso plan de formación para implantar el bilingüismo. ABC.es

Edición Toledo. Retrieved

from http://www.abc.es/toledo/20140123/abcp-junta-prepara-ambicioso-plan-20140123.html

Instrucciones

relativas al funcionamiento de los programas lingüísticos en lenguas

extranjeras en centros plurilingües sostenidos con fondos públicos de

Castilla-La Mancha para el curso 2015/2016. (2015).

Dirección General de Recursos Humanos y Programación Educativa. Consejería de

Educación, Cultura y Deportes de Castilla-La Mancha.

Krashen, S.

(1996). Surveys of opinions on bilingual education: Some current issues. Bilingual Research Journal, 20 (3-4), 411-431.

Lasagabaster, D. & López Beloqui, R. (2015). The Impact of type of approach (CLIL versus EFL)

and methodology (Book-based versus Project work) on motivation. Porta

Linguarum, 23, 41-57.

Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J.M. (2009). Language attitudes in CLIL and traditional EFL classes. International CLIL Research Journal, 1 (2). Retrieved from http://www.icrj.eu/12/article1.html

Ley 7/2010, de 20 de julio, de Educación de Castilla-La

Mancha. Presidencia de la Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha.

Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la mejora de la

calidad educativa (LOMCE). Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Gobierno

de España.

Lorenzo, F., Trujillo, F., & Vez,

J.M. (2011). Educación bilingüe:

Integración de contenidos y segundas lenguas. Madrid: Editorial Síntesis.

Los

Programas de Educación Bilingüe en la Comunidad de Madrid. Un estudio

comparado. (2010). Consejo Escolar. Madrid: Publicaciones Consejería de

Educación Madrid.

MacIntyre, P. D. (2007). Willingness to communicate in a second

language: Individual decision making in a social context. Barcelona (March,

2007).

Madrid,

a Bilingual Community 2014-2015. (2015). Consejería de

Educación, Juventud y Deporte. Dirección General de Innovación, Becas y Ayudas

a la Educación. Comunidad de

Madrid.

Nieto Moreno de Diezmas, E. (2016). The impact of CLIL on the acquisition of the learning

to learn competence in secondary school education in the bilingual programmes

of Castilla-La Mancha. Porta Linguarum, 25, 21-34.

Nikula, T., Dalton-Puffer, C., &

García, A. L. (2013). CLIL classroom discourse: Research from Europe. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 1(1), 70-100.

Orden 07/02/2005. Por la que se crea el Programa de Secciones

Europeas en los centros públicos de Educación Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria

de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla- La Mancha. Consejería de Educación y

Ciencia de Castilla-La Mancha.

Orden 13/03/2008. Por la que se regula el desarrollo de

Secciones Europeas en los centros públicos de Educación Infantil, Primaria y

Secundaria de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla- La Mancha. Consejería de

Educación y Ciencia de Castilla-La Mancha.

Orden 16/06/2014. Por la que se regulan los programas

lingüísticos de los centros de Educación Infantil y Primaria, Secundaria,

Bachillerato y Formación Profesional sostenidos con fondos públicos de

Castilla- La Mancha. Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes de Castilla-La

Mancha.

Ordóñez, C.L. (2011). Education for

bilingualism: Connecting Spanish and English from the curriculum, into the

classroom and beyond. Profile,

13, 147-161.

Plan de Plurilingüismo de Castilla-La

Mancha. (2010). Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes de Castilla-La

Mancha.

Promoting Language Learning and

Linguistic Diversity: An Action Plan 2004-2006. Commission of the European

Communities. Brussels, 24.07.2003 COM (2003) 449 final.

Ramos, F. (2007). Opinions of

students enrolled in an Andalusian bilingual programme, on bilingualism and the

programme itself. Revista

Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 9 (2). Retrieved from http://redie.uabc.mx/vol9no2/contents-ramos2.html

Richards, J.C., Schmidt, R. (2010). Longman dictionary of language teaching and

applied linguistics. London: Longman (Pearson Education).

Ruiz de Zarobe, Y., & Jiménez

Catalán, R. M. (Eds.). (2009). Content and language integrated learning:

Evidence from research in Europe (Vol. 41). Multilingual Matters.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E.L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations:

Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 25,

54-67.

Schumman, J.H. (1997). The neurobiology of affect in language.

Oxford: Blackwell.

Weiner, B. (1985).

An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92 (4), 548-573.

Wechem, M. van, Halbach, A. (2015). Don’t worry mum and dad… I will speak

English! La guía del bilingüismo del British Council School. Macmillan Education: Universidad de

Alcalá.

ATTACHMENTS

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR STUDENTS

We are carrying out a research on students, parents

and teachers´attitudes towards English and bilingual programmes in secondary

education. Please, tick the most appropriate digit according to the level of

your agreement with the item described. The

survey is confidential and the responses will be used only for research

purposes.

|

1 |

Totally

disagree |

|

2 |

Disagree |

|

3 |

Neither

agree, nor disagree |

|

4 |

Agree |

|

5 |

Completely

agree |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. I like studying English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. I like

learning content subjects in English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. The

contents that I learn through English will be helpful for my future. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. I

think that studying content subjects through English is difficult. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. I use

English outside the school. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. I

would like more subjects to be included into the bilingual programme. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. My family considers English to be an important

issue. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. My

family encourages me to study English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. The

use of English in bilingual subjects does not affect my grades. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10. I

consider my level of English has improved thanks to the bilingual programme. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

11. I get

nervous when speaking English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12. I

would like to continue studying English when I finish my secondary school

studies. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

13. I

like learning English as it helps me to communicate with people from other

countries. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14. I am

interested in learning about the culture of English-speaking countries. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

15.

Students of bilingual programmes have advantages over those of monolingual

programmes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

16.

English will help me to get a good job in the future. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

17. I

would like more languages to be included into the bilingual programme. |

|

|

|

|

|

Please, answer the following questions briefly.

Comment the most positive aspects of the bilingual programme.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Comment the most negative aspects of the bilingual programme.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR TEACHERS

We are carrying out a research on students, parents

and teachers´ attitudes towards English and bilingual programmes in secondary

education. Please, tick the most appropriate digit according to the level of

your agreement with the item described. The

survey is confidential and the responses will be used only for research

purposes.

|

1 |

Totally

disagree |

|

2 |

Disagree |

|

3 |

Neither

agree, nor disagree |

|

4 |

Agree |

|

5 |

Completely

agree |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. The

bilingual programme contributes improving the general quality of education. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. The

bilingual programme contributes improving the level of English of the

students. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.

Teaching a non-linguistic subject in English requires an important change of

methodology. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. The

teacher training programmes on bilingual methodology available for teachers

are adequate. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.

Parents´involvement into the bilingual programme is of outmost importance. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. I find

difficult to motivate my students to study non-linguistic subjects in

English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. My

students show a positive attitude towards the use of English in the

classroom. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. My

students feel anxious when they are asked to speak in English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. The

materials available for teachers of non-linguistic subjects in English are

adequate. |

|

|

|

|

|

Please, answer the following questions briefly.

Comment the most positive aspects of the bilingual programme.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Comment the most negative aspects of the bilingual programme.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR PARENTS

We are carrying out a research on students, parents

and teachers´ attitudes towards English and bilingual programmes in secondary

education. Please, tick the most appropriate digit according to the level of

your agreement with the item described. The

survey is confidential and the responses will be used only for research

purposes.

|

1 |

Totally

disagree |

|

2 |

Disagree |

|

3 |

Neither

agree, nor disagree |

|

4 |

Agree |

|

5 |

Completely

agree |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. I

encourage my child to use English in his/her free time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. It is

important to study English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. I

consider that the bilingual programme has contributed positively to the level

of English of my child. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. When

my child started the bilingual programme I was worried that it would affect

negatively his/her grades. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. The

bilingual programme motivates students to study English. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. The

knowledge of English will be helpful for my child´s future work. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. It is

important for my child to continue studying English after the secondary

school. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. Students

of bilingual programmes have an advantage over those studying in monolingual

programmes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. It is

important for my child to know about the culture of English-speaking

countries. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10. The

bilingual programme has improved my child´s attitude towards English. |

|

|

|

|

|

Please, answer the following questions briefly.

Comment the most positive aspects of the bilingual programme.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Comment the most negative aspects of the bilingual programme.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………