Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, Vol. 7(1)ISSN 1989 – 9572

USING STUDENTS´FEEDBACK TO EVALUATE TEACHERS´EFFECTIVENESS

USO DE LA RETROALIMENTACIÓN DE LOS ESTUDIATIENTES PARA EVALUAR LA EFICACIA DE LOS DOCENTES

Sing Ong Yu, Southern University

College, Malaysia

ysong@sc.edu.my

Abstract

This

paper aims to explore the effectiveness of students’ feedback as a teacher

evaluation tool. An effective teacher evaluation system should incorporate multiple

the feedback results do not fully reflect the teaching efficiency of

teachers. Students’ assessment of teachers must support valid inferences of

teachers’ effectiveness and is one of the many tools of teacher evaluation. The

author also argues that for a teacher measures of teachers’ performance. Currently, all students evaluate lecturers

teaching at both the diploma and degree levels using the same set of

questionnaires. As the entry requirements for the two classes of students are

different,evaluation model to be effective, the

university needs to look at other measures such as student achievement, content

knowledge, instructional planning and delivery, and classroom management.

Keywords

Teacher evaluation; Student´s feedback, Classroom management; Teaching effectiveness;

Achievement

Resumen

Este artículo tiene como objetivo

explorar la eficacia de la retroalimentación de los estudiantes como una

herramienta de evaluación de los maestros. Un sistema eficaz de evaluación

docente debe incorporar múltiples medidas de desempeño de los maestros. En la

actualidad, todos los estudiantes evalúan los profesores que enseñan tanto a

nivel de diplomatura como de grado utilizando el mismo conjunto de

cuestionarios. A medida que los requisitos de entrada para las dos clases de

los estudiantes son diferentes, los resultados de retroalimentación no reflejan

totalmente la enseñanza eficiente de los maestros. La evaluación estudiantil de

los maestros debe ser apoyada con inferencias válidas de la eficacia de los

profesores y ser una de las muchas herramientas de evaluación de los maestros.

El autor también sostiene que para un modelo de evaluación de los maestros sea

eficaz, la universidad tiene que mirar a otras medidas como el rendimiento de

los estudiantes, el conocimiento del contenido, la planificación de la

instrucción y la distribución, y la gestión del aula.

Palabras Clave

Evaluación del professor; Retroalimentación del estudiante; Gestión del

aula; Eficacia de la enseñanza; Éxito

|

Yu, S.O. (2016). Using students’ feedback to evaluate teachers’ effectiveness. Journal

for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, Vol. 7(1). 182 – 192.

|

File PDF

1. Introduction

The effectiveness of the

evaluation process depends largely on the proper design and assessment of the

evaluation criteria. Successful feedback mechanisms demands attention to

identifying competencies of actors such as lecturers as well as developing

evaluation criteria specific to different groups of respondents such as

students. Lecturers often expressed frustrations about the mechanisms of the

teacher evaluation process by students. The timing of the feedback process in

the first half of the semester did not give sufficient time for both lecturers

and students to know each other well. Lecturers need time to engage the

students fully to understand their learning needs and capabilities while

students require time to adapt to the teaching styles of lecturers. Feedback

has to be given as soon as possible when the learning task is completed to

allow lecturers to internalise the feedback findings and make any changes to

their teaching styles. The current system of not revealing the various

component scores of the feedback process to the lecturers is counter-productive

as lecturers do not know which aspects of their teaching need to be improved

and which aspects are appreciated by students. For the feedback process to be

effective, lecturers need to receive timely and substantive information about

their performance. The absence in providing these outcomes will result in

concerns among lecturers that the appraisal process is just an administrative

exercise which does not fully reflect their competencies.

Human resources policies need

to be adjusted to give considerable attention to sound procedures to assess

performance against certain standards. The evaluation process has to be both

measurable and reliable. The current lecturer evaluation process is unreliable

as it does not take into account the differences in academic standing between

diploma and degree level students. The entry requirements into a diploma

programme are lower than a degree program. Students entering into a degree level

program have two additional years of high school education as compared to those

enrolling in a diploma level program.

Table 1. Entry Requirements

|

Diploma

|

Equivalent of 3 “O Level” subjects

|

|

Degree

|

Equivalent of “A Level” or Diploma

|

This

paper proposes a conceptual framework which integrates formative assessment and

summative assessment. The formative assessment methods that lecturers use to

conduct evaluations of students’ comprehension and academic progress help to

validate the summative assessment of teaching which are recorded as feedback

scores of teachers. Combining both student improvement and accountability

functions into a comprehensive lecturer evaluation process requires an

adjustment in human resource policies.

The traditional

approach to teacher evaluation process is formative in nature. The formative

assessment monitors student learning to provide ongoing feedback that can be

used by lecturers to improve their teaching and by students to improve their

learning. Summative assessment evaluates student learning at the end of an

instructional unit through exam or a final project. Our framework combines an

element of summative assessment of lecturers by students through the use of

student evaluation questionnaire (Fig 1).

More

importantly, research studies have shown that gains in student achievement are

also attributed to other factors such as school environment, school culture and

individual student needs and motivation (Yu, 2016)

Fig 1. General

Conceptual Framework2. Significance

of this study

This study

recognises that lecturers’ evaluation by students is part of the overall

assessment of lecturers’ performance. Universities often use questionnaires as

a student feedback tool. However, universities failed to differentiate the

academic standing of the classes of students responding to the questionnaires.

This paper stresses that the differences in feedback responses by diploma and

degree students are due to the different academic standings of the two classes

of students. Universities’ administrators should re-examine the feedback

processes for the different classes of respondents in relation to its

effectiveness in improving the teaching and learning outcomes of both lecturers

and students.

3. Literature

review

Students’

feedback is one of the most common tool which influences learning and

achievement. Research by Natriello (1987) and Crooks (1988) have found that

substantial learning gains can be achieved when teachers introduced formative

assessment into their classroom practice. Formative assessment relates to

assessment to generate feedback on performance to improve and accelerate

learning (Sadler, 1998). Black and William (1998) noted that students’ feedback

produced significant benefits in learning and achievement across all content

areas, knowledge and levels of education.

Feedback can

only be effective if it is understood and internalised by students before it

can be used to make improvements. Very often, students do not understand the

importance of the feedback given by teachers and therefore not able to fully

comprehend the intentions of teachers and the effects they would like to

produce (Chanock, 2000). To overcome this situation, teachers should engage in

constant dialogue with students to develop their understanding of expectations

and standards. Butler (1987) noted that grading students’ performance has less

effect than giving feedbacks as students tend to compare their grades with

their peers rather than focusing on the ways to improve their tasks.

Good feedback helps teachers to improve their

performance (Yorke, 2003). Teachers need good information about how their

students are progressing so that they can refine their teaching accordingly. An

effective feedback mechanism facilitates the development of self-assessment

(reflection) in learning as well as encourages positive motivational beliefs

and self-esteem (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). Tram and Williamson (2009)

noted two approaches in the evaluation of teaching: teaching-focused and

learning-focused. Teaching-focused evaluation emphasizes on the course content,

activities and teaching techniques as well as the characteristics of teachers.

Learning-focused evaluation, on the other hand, focused on the effectiveness of

the teachers to improve student learning. It measures students’ expectations,

their perceptions of the learning environment and the appropriateness of the

learning activities. Hajdin and Pazur (2012) concluded that teacher and teaching

effectiveness should be evaluated separately.

Studies by

Hattie and Timperley (2007) noted that quality feedback has significant impact

on student learning achievements. Most improvements in student learning were

recorded when students receive feedback about how to do a task effectively.

They also found that learning achievement is low when feedback focussed on “praise, rewards and punishments”. It is

most effective when the goals are measurable and achievable. Universities

should focus on how appraisal and feedback systems improve students’

performance. Measures should be developed to assess the effectiveness of the

feedback process and this include informing lecturers of the benchmarks against

which performance is assessed. Yu (2016) noted that universities need to

reculture to remain sustainable and that positive culture will facilitate staff

and student learning.

Establishing a

classroom environment that facilitates learning requires special skills from

teachers. Swartz et al., (1990) assessed teachers’ performance on five

functions: instructional presentations, instructional monitoring, instructional

feedback, management of time and management of students’ behaviour. Yu (2016)

concluded that students’ achievement has a strong effect on teachers’

motivation. The higher the student achievement, the more motivated are the

teachers. Teachers are motivated when they felt that their contribution will be

appreciated (Yu, 2012).

Developing a

comprehensive teacher evaluation tool is challenging. Isore (2009) noted that

there are costs involved at every stage of the process, from consultations with

relevant stakeholders to reaching agreements. Danielson (1996, 2007) stressed

the high costs and time of training evaluators. Heneman et al., (2006)

indicated the unwillingness of teachers and evaluators to take on additional

workload unless other workloads and responsibilities are reduced.

Research by

Shin et al. (2006) comparing the critical thinking ability of

undergraduate nursing students provided evidence that bachelor degree students

scored higher on critical thinking than associate degree and diploma students.

The study concluded that the length and content of the educational program is

important to encourage students to develop their critical thinking abilities

earlier.

Slavin et al.

(1995) identified characteristics associated with effective teachers. He

described “commitment” and “drive for improvement” as examples.

Ashton and Webb (1986) termed “self-efficacy”

as an important characteristic related to teacher effectiveness. Medley (1982)

linked teacher competence and teacher performance with teaching effectiveness.

The degree to which a teacher is effective is dependent on the goals pursued by

the teacher (Porter and Brophy, 1988).

4. Research

question

We began with

several key questions:

Are there differences in feedback scores of Diploma and Degree level students?

What could possibly be main for the differences, if any?

5. Methodology

The main goal

of the research was to highlight the differences in the response rate between

diploma and degree level students. The research study was conducted on students

of the Faculty of Business over a two semester period. The sample included 30

lecturers who are teaching at both diploma and degree levels. A total of 30

different diploma and 30 degree subjects per semester were chosen. There were

1,100 student participants in the survey. The class size per level ranges from

10 to 80 students per class. The research was based on one online survey

exercise per semester in the form of a questionnaire administered by the

Registry department.

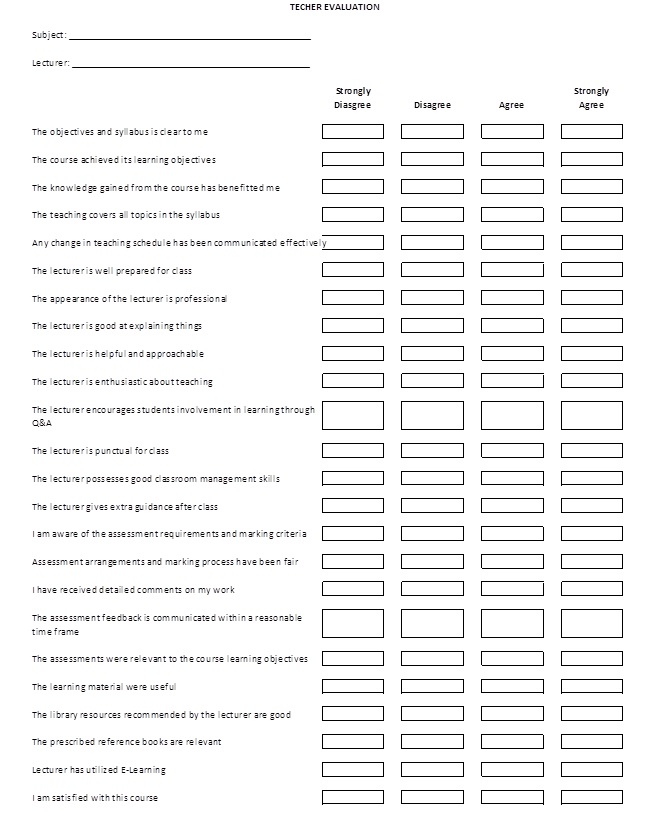

A

typical 4-point ordinal Likert scale was used by the respondent to rate the

degree of teaching effectiveness. Both the diploma and degree level students

were given the same set of questionnaire to measure the attitudes or opinions

under investigation.

The

students were asked to fill up an online survey form which consisted of 25

questions (Appendix 1). Survey respondents were asked to give their views on

how much they agree with the statements relating to delivery of curriculum,

student support, classroom management and utilization of e-learning. No

incentives were provided for the participants and their participation were

compulsory. The responses to the questionnaires were compiled by the Registry

office and an overall feedback score was tabulated for each lecturer. The feedback

scores were analysed using the IBM SPSS statistical software package.

The one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine Research Question 1 on

whether there are any significant differences between the mean scores of the

two classes of students. Research Question 2 is descriptive in nature and

relates to the entry requirements of the Diploma and Degree students.

6. Results and

discussion

Table 2. Descriptives

|

|

N

|

Mean

|

Std.

Deviation

|

Std. Error

|

95%

Confidence Interval for Mean

|

Minimum

|

Maximum

|

|

Lower Bound

|

Upper Bound

|

|

1

|

60

|

78.8757

|

7.76433

|

1.00237

|

76.8699

|

80.8814

|

51.75

|

91.50

|

|

2

|

60

|

81.8780

|

6.44937

|

.83261

|

80.2120

|

83.5440

|

51.00

|

97.00

|

|

Total

|

120

|

80.3768

|

7.26526

|

.66322

|

79.0636

|

81.6901

|

51.00

|

97.00

|

Table 2 shows the differences in the

mean for the two groups of students. The Diploma class is denoted by “1” while the Degree class is denoted by

“2” The mean score of respondents in

Diploma programs (78.87) is lower than those in Degree programs (81.87). We use

a 95% confidence interval for the dependent variable “score”. The differences in the mean scores are most likely due to

the different academic standing of the two classes of respondents. Students who

have not met the entry requirements for the Degree program are enrolled in

Diploma programs. Degree level students are those who have either met the entry

requirements or have graduated from a Diploma level program. In general, degree

level students have two additional years of high school education.

Table 3. Anova

|

|

Sum of Squares

|

df

|

Mean Square

|

F

|

Sig.

|

|

Between Groups

|

270.420

|

1

|

270.420

|

5.309

|

.023

|

|

Within Groups

|

6010.869

|

118

|

50.940

|

|

|

|

Total

|

6281.289

|

119

|

|

|

|

The output of

the ANOVA analysis showed a significance level of 0.023 (p=0.023). This is

below the 0.05 significance level and, therefore, we can conclude that there is

a statistically significant difference in the mean score between the two

classes of students.

Students’

performance measures such as test scores and assessments form an important

parameter of our framework. It occurs at the summative evaluation stage which

is normally during the mid-term and final term exam period. It can be used as a

diagnostic tool to assess students’ learning and this has implications on

teaching efficiency. The above findings gave evidence of the importance of

promoting “Critical Thinking” as a compulsory subject rather

than as an elective subject currently. It is essential for universities to

define the objectives that encourages students’ critical thinking abilities and

to develop curriculum and teaching methodologies to meet these objectives.

The evaluation

of teaching activities is important as it ensures the quality of teaching and

student learning. Different procedures are carried out to evaluate the training

objectives and competencies of lecturers in delivering teaching activities to

students. While the key elements in the evaluation model may be applicable to

both diploma and degree level students, the quantitative evaluation in the form

of feedback score needs to be adjusted for those lecturers teaching Diploma

level courses.

Students’

feedback is only one component of evaluating teachers’ teaching effectiveness.

Other measures such as student achievement, content knowledge, instructional

planning and delivery, and classroom management are equally important (Figure

2).

Fig 2. Components of

Teaching Effectiveness7. Recommendations

Universities

need to re-compute the overall feedback score of Diploma level

lecturers

through an upward reweighting of the overall score. From the results of

our

analysis, the mean differences range from 1.8% to 5.9% taking into

consideration

the standard deviations of both means. Conservatively, we would

recommend a 3%

reweighting upwards in the feedback scores of lectures teaching Diploma

level

subjects to make them more comparable to those teaching Degree level

courses. The Adjusted Feedback Scores (AFS) is represented by the

equation below:

Adjusted Feedback Scores (AFS) of Diploma level lecturers =1.03 x initial feedback score

The multiplier

of 1.03 takes into account the different academic standings of the two classes

of students and ensures more parity in the teacher evaluation processes between

Diploma and Degree level lecturers.

Another

alternative is to design different sets of questionnaires for the two classes

of students. The Diploma level students will be given one set of questionnaire

which is different from those to be completed by Degree level students. This

may involve reweighting the different components of the questionnaire. Human

Resource policies need to change to take into consideration the two classes of

excellent teachers rather than aggregating them into one indistinct class.

The ongoing

process of improving professional teaching is essential for ensuring student

learning success and this has to be the main focus of the evaluation process.

Our proposed framework recommends that the university incorporates the

following elements in a new lecturer appraisal and feedback system (Fig. 3). These include:

1. Student Performance

2. Student assessment of lecturers

3. Peer observation of classroom teaching

4. Peer collaboration

5. Self-assessment, reflection and

planning

6. Introducing Critical Thinking as a compulsory

subject at Diploma level

7. The feedback exercise to be held in the

second half of the semester

Fig 3. Proposed

conceptual framework for differentiated teacher evaluation

The purpose of

lecturer evaluation needs to be conveyed clearly to students. Both lecturers

and students need to know what aspects of lecturer evaluation are monitored. At

the same time, the outcomes objectives, performance indicators and reference

standards should be make known by the human resource department to the

lecturers. Specific goals are more meaningful than general ones as they help to

focus on students’ achievements and feedback. They also assist to reduce the

gap between actual and desired levels of performance.

Lecturers’

professional profiles, including specialised knowledge and skills should be

listed clearly and measured against reference standards which are made known to

lecturers. The accountability function of lecturer evaluation holds lecturers

accountable for their performance. The outcome of a good feedback should result

in some form of recognition and reward for it to be effective. Conversely, a

poor feedback may result in some kind of sanctions against the lecturer. This

policy has to be transparent to lecturers to avoid any feeling of demotivation

or disgruntlement. University leaders have the ability to motivate teachers and

must create an environment that promotes change (Yu, 2009). They should

encourage the use of the feedback process as a legitimate tool for lecturer

development and avoid any unnecessary bureaucratic procedures associated with

the reward mechanism.

Our proposed

conceptual framework includes “Critical

Thinking” as compulsory subject

rather than an elective subject to develop the critical thinking skills of all

students. For the evaluation feedback to be effective, the timing of the

feedback exercise should be moved to the second half of the semester to enable

students to adapt to the teaching styles of lecturers. The present system of

not revealing to the lecturers the components of the feedback scores needs to

be changed as lecturers are unaware of which aspects of their teaching need

improvement. Only through a comprehensive understanding of their teaching

capabilities and inadequacies can they improve their performance.

8. References

Ashton, P. & Webb, N. (1986). Making a

difference: Teachers’ sense of efficacy and student achievement (Monogram).

White Plains, NY: Longman.

Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (1998) Assessment and

classroom learning, Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7-74.

Butler, R. (1987) Task-involving and ego-involving

properties of evaluation: effects of different feedback conditions on

motivational perceptions, interest and performance, Journal of Educational

Psychology, 78(4), 210-216.

Chanock, K. (2000). Comments on essays: do students

understand what tutors write? Teaching in Higher Education, 5(1),

95-105.

Crooks, T. J. (1988). The impact of classroom

evaluation practices on students, Review of Educational Research, 58(4),

438-481.

Danielson, C. (1996, 2007), Enhancing Professional

Practice: a Framework for Teaching, 1st and 2nd editions, Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), Alexandria, Virginia.

Hajdin, G and Pazur, K. (2012) Differentiating between

students evaluation of teacher and teaching effectiveness. Journal .of

Informational and Organizational Sciences, 36(2), 123-134.

Hattie, J. and Timperley.H. (2007). The Power of

feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77, 81-112.

Heneman, H., A. Milanowski, S. Kimball and A. Odden

(2006), “Standards-Based Teacher Evaluation as a Foundation for Knowledge- and

Skill-Based Pay”, Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) Policy

Briefs RB-45.

Isoré, M. (2009), “Teacher Evaluation: Current

Practices in OECD Countries and a Literature Review”, OECD Education Working

Paper No.23, OECD, Paris. Available from www.oecd.org/edu/workingpapers

Medley, D. M. (1982). Teacher effectiveness.

H.E.Mitzel (Ed,), Encyclopedia of Educational Research (5th

ed.), 1894-1903. New York: The Free Press.

Natriello, G. (1987). The impact of evaluation

processes on students, Educational Psychologist, 22(2), 155-175.

Nicol, D.J. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice, Studies in Higher

Education, 31:2, 199-218, DOI: 10.1080/03075070600572090

Porter, A.C. & Brophy, J. (1988) Synthesis of

research on good teaching: Insights from the work of the Institute for Research

on Teaching. Educational Leadership, 45(8), 74-85.

Sadler, D. R. (1998) Formative assessment: revisiting

the territory, Assessment in Education, 5(1), 77-84.

Shin, S., Ha, J., Shin, K., and Davis, M (2006).

Critical thinking ability of associate, baccalaureate and RN-BSN senior

students in Korea. Journal of Nursing, 26 (9), 354-361.

Slavin, R.E.

(1987). Ability grouping and student achievement in elementary schools: A

best-evidence synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 57(3), 293-336.

Swartz, C.W.,

White, K.P., Stuck G.B., and Patterson, T. 1990. The Factorial Structure of the

North Carolina teaching performance appraisal instruments. Educational and

Psychological Measurement, 50,175-182.

Tram, D.N.

& Williamson, J. (2009). Evaluation of teaching: hidden assumptions

about conception of teaching, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference

of Teaching and Learning (ITCL), INTI University College, Malaysia.

Yorke, M (2003) Formative assessment in higher

education: moves towards theory and the enhancement of pedagogic practice, Higher

Education, 45(4), 477–501.

Yu, S.O. (2009). Principal leadership for private

schools improvement: The Singapore perspective. The Journal of international

Social Research, 2(6), 714-749.

Yu, S.O. (2012). Complexities of multiple paradigms in

higher education leadership today. Journal of Global Management, 4(1),

92-100.

Yu, S.O (2016). Conundrum of Private Schools in

Singapore. International Journal of Business and General Management, 5(3),

37-64.

Yu, S.O. (2016). Reculturing: The key to

sustainability of private universities. International Journal of Education

and Research, 4(3), 353-366.

APPENDIX 1